|

Chapter 1:

Introduction to the |

Virtual Anthropology Lab Handbook

Return to MODULE PAGE Return to VIDEO LAB |

by James Stanlaw (Primary Author) & David Leech Anderson

You are about to become a field anthropologist doing research on color terms. Color terms have been a source of fascination for anthropologists since at least the turn of the 20th century, when it was noticed that different cultures divide the color spectrum in different ways. For instance, some languages have only one term (what English-speakers refer to as a 'grue'-term) to refer to the range of colors that English-speakers describe with the two different terms of 'green,' and 'blue', while there are other cultures that use two or three terms to refer to those colors that most English-speakers would refer to with the single term 'blue.' What explains the diversity? And how much actual diversity is there? Is the number of color terms and the way the color-categories "cut-up" the color spectrum entirely relative to the interests of the culture? Or are there universal constraints of some kind that cause there to be identifiable regularities in the way all cultures organize and describe colors? And what significant conclusions might we draw based on either answer to that question?

As you proceed through this lab, keep in mind that while different theories about the nature of color terms have waxed and waned in popularity over the years, it continues to be a field where there is healthy controversy. We hope to take you into the middle of contemporary debates, allow you to "gather" some data, and let you decide which side, if any, you are on.

Soon you will become an informant in a protocol or excercise and then you will conduct a research study yourself, gathering data from three (virtual) persons who speak different languages and come from different cultures. Finally, you will compare and contrast color data from 10 different languages that give a good overview of the very different ways that languages deal with color. But first you will need to read a bit about the debate you will soon be joining. Two essays follow.

ESSAY #1: Reality, Experience, Thought and Language: The Debate

As we explore the nature of the mind and brain, we discover some of the "big questions" that have occupied the thoughts of philosophers, theologians and scientists since the dawn of human reflection. Some of these questions are recognized as a legitimate part of the study of cognitive science by most researchers in the field. (They are often described as "foundational issues.") Some other questions are more controversial.

Big questions arise when we begin to consider the basic situation in which we find ourselves as rather small creatures living in a vast universe. We are confronted with four inescapable features of our situation as we consider the world and how it is that we come to know about it.

- REALITY / THE WORLD: We inhabit

a universe populated with an amazing array of objects that we see, use,

play with and think about.

- EXPERIENCES: We

are finite creatures with limited yet reliable access (through our 5

senses) to the

world outside of us. Our eyes cannot see all frequencies of light; nor

can we see every corner of the universe. Though we can't know everything,

we do

seem able to learn quite a bit about reality.

- THOUGHTS: Our thoughts somehow have the capacity

to represent objects in the world outside of us and thus enable us to "think

about" those objects

which our senses reveal to us.

- LANGUAGE: Natural human languages (English, Spanish, etc.) are publicly accessible systems of symbols that enable us to express to others our thoughts about the external world.

The Priority of the World (Realism or Objectivism)

What exactly is the relationship between these four elements? One natural way to understand the situation - often called "realism" or "metaphysical realism" or "objectivism" - is to assume that there is a pecking order (a "hierarchy") with the items higher on the list having a kind of priority over the ones beneath them. On this assumption, THE WORLD has priority over the rest. The universe existed before humans came on the scene. Whatever objects exist and whatever properties those objects possess - they were what they were before humans experienced them, thought about them, or spoke about them with language. Humans simply discover what is already there, waiting to be found. Philosophers articulate this view by saying that reality exists independent of the operations of the human mind; it is a "mind-independent" reality.

Assuming an objective world with pre-existing objects, our experiences get us causally connected to those objects and give us (largely) reliable information about them. Our thoughts enable us to believe truths about these objects and to reason about them. If it weren't for other people, we wouldn't even need language. But if we want to share our thoughts with others, we need a public language that offers conventional symbols that express our thoughts to others and that we can use to label the independently existing physical objects. One label for a physical object is as good as another and becomes irrelevant as soon as it has succeeded in pointing us to the object itself - which is the same for everyone: a pre-existing, mind-independent entity.

The collection of theories just described offers one perspective on the nature of thought, language and reality. Let's call it "The Priority of the World" Perspective. As described, it remains a rather loose, sketchy view that few researchers in cognitive science would embrace in its entirety. However, as a kind of benchmark, it can be used to measure a person's perspective as being either closer or further from that general view of things.

To take one specific example, there is a very popular theory within contemporary cognitive science that is more or less congenial to this perspective in its stance on the relationship between thought and language: It is Jerry Fodor's "language of thought" (LOT) hypothesis. This theory holds that our thought has priority over language insofar as our thought-life is not dependent upon natural languages like English and Spanish. We do not literally "think" in English. Instead, our mind/brain uses its own internal language (called "mentalese" by Jerry Fodor) to represent objects, to reason, etc. On this view the terms of a natural language simply express in a public symbol-system what the brain has already represented to itself in a natural system (implemented in the brain). If there is a "language of thought," then it is at least plausible to think that the similarity among all humans in the structure of their brains and genetic make-up will contribute a strong influence from nature that will constrain (at least to some degree) the extent to which the interests and beliefs of my particular culture can effect me through its nurturing influence. Further, if it is the objective, mind-independent world itself that supplies the "content" of many of our thoughts, then the fact that we inhabit the same world will also go far to ensure that the content of your thoughts will overlap considerably with the content of my thoughts, whether you are from Cleveland or Cameroon. While Fodor himself would not necessarily license this rather strong application of his LOT thesis, this general picture clearly has its advocates.

In contrast to the previous picture, there are those who believe that we literally "think" in English (or some other natural language), thus giving language a more influential place in the hierarchy than it would otherwise have. In fact, before we go further, let's consider another broad perspective on the relationship between reality, experience, thought, and language that offers a stark contrast to the "priority of the world" perspective, just described.

The Priority of Language (Relativism)

What reasons might one have for rejecting any or all of the theories described in the "priority of the world" perspective? This view presupposes that the world is "cut-up" into objectively real, fixed kinds of objects ("natural kinds" like oak trees) and unique individual objects (like the single oak tree in our quad, let's call it 'Woody'). So long as a language has a word to refer to the tree that we call, 'Woody,' and to the natural kind that we call 'oak trees' - the content of our thoughts will be the same - whether we speak English, Spanish, or the Cameroon language of Ejagam.

But what if things don't work quite that way. What if the natural language that one speaks actually shapes and colors the way one thinks about the world? What if the names and properties, the concepts and categories with which we conceive the world are not given to us by a natural system of representation, common to all human brains but instead are given to us by the natural languages that we speak (English, Spanish, Ejagam) and that in turn cause us to conceive of "the World" in fundamentally different ways?

You might have already begun to consider the implications of this view for the hierarchy that we offered in our initial list. Instead of "reality" exerting itself on the rest of the system, ensuring that experiences, thought and language will always be "about" one-and-the-same set of mind-independent objects, we have "language" exerting itself on the rest of the system, ensuring the thought, experience, and the World itself bears the stamp of the language that conceives it. This general view, which we'll call "The Priority of Language" perspective, flips the list on its head.

- LANGUAGE: Natural human languages (English, Spanish, Ejagam, etc.) implement

a set of concepts and categories (what philosophers often call a "conceptual

scheme") which shape and color the way people think about and even experience

the world around them.

- THOUGHTS: The concepts and categories that enable

us to think about objects in the world are neither innate nor generated

by non-linguistic experiences but are instead supplied by the natural

languages that we speak and

the social institutions that support them.

- EXPERIENCES: Our experiences of the world are shaped by the concepts

and categories that we use to organize and make sense of the input

from our

five

senses. The world that we experience - the only world that we know

- is colored by (some would go so far as to say that it is constituted

by) the

conceptual

scheme that our language embodies.

- REALITY / THE WORLD: We inhabit a universe populated with an amazing array of objects that we see, use, play with and think about. These objects do not exist independent of the cognitive activity of human beings, but are, rather, shaped by the beliefs and interests of our culture as reflected in the concepts and categories embedded in our language.

Now, it is important to appreciate that few researchers would embrace this entire family of claims. The "priority of language" perspective is offered as the opposite extreme of the "priority of the world" perspective and is best thought of as a measuring stick to help assess where particular researchers stand on a particular question. All things considered, a majority of people defend more subtle positions lying somewhere between the extremes. And yet, on specific issues, these broader categories of "objectivism" vs. "relativism" prove quite helpful in understanding the dispute. We turn, now, to a dispute - still very much alive - in which these two perspectives go head-to-head.

The Dispute over "Color Terms": Relativism vs. Universalism

The "world" that we inhabit comes to us in glorious Technicolor. But what is the nature of color and the color categories that we use to distinguish them? Are "red" and "blue" distinct, objective features of the world? Are they universal categories that impose themselves on all human beings in all cultures? Does nature determine that "red" is a fundamental category distinct from "blue" or are color categories arbitrary boundaries drawn relative to the interests of one's culture?

I have just described things from one "philosopher's" perspective. But attempting to explain the phenomena and experience of color is something that people from many different fields have investigated, from psychology to neurology. Is there empirical evidence to support either of the objectivism or relativism claims just mentioned? Today, you are going to explore this question the way anthropologists and linguists have.

You are going to explore these questions by becoming a linguistic anthropologist. You will study a brief history of the dispute between "relativists" and "universalists," you will become a subject in a field study, and then you will do field research yourself by interviewing three informants from three different cultures. You will then study data from ten different languages/cultures and be asked to reflect on what the data shows. Are there objective constraints that determine the color categories that we use, or are color categories ultimately determined by the language that we speak and the relative interests of the cultures to which we belong? Does the debate between "universalists" and "relativists" about color terms have anything to do with the philosophical debate between "realists" and "idealists"? Some will say 'Yes.' Some will say, 'No.' The next essay, written by James Stanlaw, a linguistic anthropologist, will begin your training.

ESSAY #2: Colors and Culture

The "Puzzle of Color" and the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

Simply put, this module is about how and why people choose names for colors, and how humans might perceive and interpret the visual world. Answers to these questions are not as obvious as you might at first think, and I believe you will come to see as we go along that the "puzzle of color," as an early researcher called it, is more than just an esoteric problem in experimental psychology or a quaint philosophical paradox. Color terminologies have been a source of fascination for anthropologists from at least since the turn of the 20th century, when the early ethnographers on the seminal Torres Straits expedition noticed that "non-Western" peoples often have very different ways of dividing up the color spectrum. For instance, some languages, it was found, would blend blue and green colors under a single term, while others would break up, say, the English reds using three or four separate names. It was puzzling to find that so "natural" and neutral a stimulus as the color spectrum could be divided up--that is, named--in hundreds of different ways.

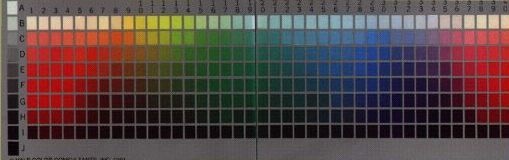

Since the 1950's, a common way of systematically investigating colors was to use an array of Munsell color chips, a common commercially available set of accurate and consistently-reproduced color standards used by scientists, engineers and artists (similar, in a way, to the sample paint swashes found in most hardware stores, but scientifically calibrated).

When such an array was presented to informants, it was found that almost any kind of configuration of color names was possible. Until the late 1960's, color was taken as the best--if not the only--empirically-grounded evidence for linguistic relativism. That is, it was thought that languages and cultures could vary in their color nomenclature almost without constraint, and that there would be no a priori way of knowing how any particular color term system might appear. Indeed, the variety found in color nomenclature seemed to indicate that there is nothing inherent in either human perceptual facilities or the physical world that would compel a language to name some domain in any particular fashion.

One very influential way of expressing the "relativist" perspective was advanced by Edward Sapir and his talented student, Benjamin Lee Whorf. While there is no simple, clear articulation of the position, their names have become associated with what is now called "the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis." A basic feel for the position is available in a famous quote from Sapir:

Language is a guide to "social reality." ... Human beings do not live in the objective world alone, nor alone in the world of social activity as ordinarily understood, but are very much at the mercy of the particular language which has become the medium of expression for their society. ... The fact of the matter is that the "real world" is to a large extent unconsciously built up on the language habits of the group. No two languages are ever sufficiently similar to be considered as representing the same social reality. The worlds in which different societies live are distinct worlds, not merely the same world with different labels attached. (Sapir 1929[1949]:162).

Sapir gives further support to the "priority of language" when he says:

Language ... not only refers to experience largely acquired without its help but actually defines experience for us by reason of its formal completeness and because of our unconscious projection of its implicit expectations into the field of experience. ... Such categories as number, gender, case, ... and a host of others, ...are systematically elaborated in language and are not so much discovered in experience as imposed upon it because of the tyrannical hold that linguistic form has upon the orientation in the world. ... Inasmuch as languages differ very widely in their systematization of fundamental concepts, they tend to be only loosely equivalent to each other as symbolic devices and are, as a matter of fact, incommensurable ... (Sapir 1931[1964]:128).

The term "Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis" was never used in the lifetimes of either man, probably because neither ever synthesized their notions of linguistic relativity in a formally precise way. However, the following postulates probably underlie most versions of the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis:

Linguistic equality. All languages are equal. There are no superior or inferior languages. No language is "good" or "bad, or "beautiful" or "ugly," except for personal opinion. Likewise, no language is "pre-logical" or "primitive" in any way. Indeed, anything can be said in any language (though different languages may have different words or grammatical tools to do so).

Linguistic relativism. Each language's encoded categories are unique. That is, the distinctions made in one language are not necessarily found in another.

Linguistic determinism. Language structures thought or thought is dependent upon language. How we talk determines how we think.

The primacy of language in perception. There is no such thing as pure perception. All perception involves an act of interpretation and all interpretation is mediated through language. Thus, ultimately perception is predicated upon language.

Linguistic arbitrariness. Languages select and create their categories in a largely random way. To be sure, there are environmental and cultural influences. However, there is nothing in a language that would allow us to predict in any a priori way ahead of time what classifications would be found.

The inevitability of linguistic diversity. Because language structures thought, and different languages have different categories, and these categories are largely arbitrary, it is obvious that great linguistic diversity is going to develop.

Linguistic experientialism. The language one speaks determines how one sees and experiences reality. If language determines world view, then people speaking different languages live in different phenomenological "worlds." (Today, the term “linguistic relativity” is often used for the argument—at least in its strongest form—that says that speakers of different languages live largely in incommensurate worlds.)

The "relativist" perspective on color terms was the dominant influence from roughly 1920 to 1970. Starting in the late 1960's and early 1970's, however, new research data challenged that orthodoxy.

The Berlin and Kay Challenge

In 1969, Brent Berlin and Paul Kay, two anthropological linguistics at the University of California at Berkeley, challenged the dominant, relativist, position when they presented evidence that suggested that there were rather severe restrictions on how color names-and apparently, then, color concepts-could be used. If the notion of "color term" was restricted to certain monolexemic productive lexemes, there appeared to be only about a dozen terms, at most, that any language might have; indeed, a majority of the world's languages would probably have eleven or fewer of these basic terms. There also seemed to be a cross-culturally universal sequence as to how a language would acquire new color categories. WHITE's and BLACK's were always the first terms found; RED's always came next (before YELLOW's or BLUE's), and PINK's or ORANGE's were always added last. And while the ranges of these terms could vary greatly on an array, certain color chips seemed to have universal psychological salience, even if the language in question had no actual term for that color. For example, while the Dani of New Guinea are said to have only two "basic" colors (WHITE, or all the light colors, and BLACK, or all the darks), prototypical "fire-engine" RED chips are recalled much better than other less typical RED's. Physiological and bio-psychological explanations were proposed to account for these findings. (Don't worry if you do not know some of the jargon; these notions are all fairly straightforward, and will be explained with diagrams later. And there are some reasons why I am using capital letters to label colors here which I will also explain later.)

In the thirty years since the original Berlin and Kay work (1969; 1991), some several hundred studies have generally supported their original findings, albeit with some modifications (cf. the World Color Survey 1991; Kay, Berlin, and Merrifield 1991). Today, this universalist account is probably considered to be the standard model of color nomenclature against which all data and other models are evaluated. Though modified and refined, the universalist arguments of Berlin and Kay have remained principally in tact, though there are, of course, some serious philosophical challenges (cf. Saunders 1992; Saunders and van Brakel 1996).

Although there continue to be many critics of the view, the following conclusions were defended by Berlin and Kay in their 1969 work and continue to have strong support within the field:

- All languages have terms for BLACK and WHITE

- If

a language has three basic color terms, they are, roughly:

BLACK, WHITE, and RED.

- Generally, if a language has four basic color terms, they will be:

BLACK, WHITE, RED and GREEN or YELLOW.

- If a language

has five basic color terms, they will be: BLACK, WHITE,

RED, GREEN and YELLOW.

- If a language has six basic color terms, they will be:

BLACK, WHITE,

RED, GREEN.YELLOW and BLUE.

- If a language has

seven basic color terms, they will be: BLACK, WHITE,

RED, GREEN.YELLOW, BLUE and BROWN.

- If a language has eight or more basic

color terms, they will be: BLACK, WHITE,

RED, GREEN.YELLOW, BLUE, BROWN and PURPLE, PINK, or ORANGE in

any order. That is, a languages eighth basic color term may be PURPLE,

PINK, or ORANGE. Its ninth term will be one of the remaining two, and

its

tenth term

will be whichever term is remaining.

- The color term, GREY, can

appear anywhere - it is a wild card.

- Apparently, eleven is the

maximum number of basic color terms.

- The progression of basic color terms is summarized in the chart, below:

Green or Yellow |

--> |

Red |

--> |

Green or Yellow |

--> |

Yellow or Green |

--> |

Blue |

--> |

Brown |

--> |

Pink &/or Organge

&/or Purple &/or Grey |

I. |

II. |

III. |

IV. |

V. |

VI. |

VII. |

In this Virtual Anthropology Lab, you are going to become first a subject in a Berlin-Kay style study, and then you will become a researcher, interviewing informants from three different cultures. Finally you will study data from ten different languages. You will examine the data and come to your own conclusions about how persuasive you find the Berlin-Kay theories and where you stand in the general dispute about the relationship between reality, experience, thought and language. Before you begin the data-gathering process, you need to read just a bit more about the physics of light and the research methodology that you will use in gathering data about color terms.

BIBIOGRAPHY

Berlin, Brent, and Paul Kay. Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Growth. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1969.

Berlin, Brent, and Paul Kay. Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Growth, 2nd. ed. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1991.

Carroll, John, ed. Language, Thought and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. Cambridge: MIT Press. 1956.

Kay, Paul, Brent Berlin, and William Merrifield. Bicultural Implications of Systems of Color Naming. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 1:12-25. 1991.

Kay, Paul, and Willett Kempton. "What Is the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis?" American Anthropologist 86:65-79. 1984.

Munsell, Albert. A Color Notation. Baltimore, MD: The Munsell Color Company. 1905.

Munsell Book of Color. Macbeth/ Munsell Color: New Winsor. NY. n.d.

Sapir, Edward. "The Status of Linguistics as a Science." Language 5:207-214. 1929. also in Selected Writings of Edward Sapir in Language, Culture, and Personality. David Mandelbaum, ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1949. pp. 160-166.

Sapir, Edward. "Conceptual Categories in Primitive Languages." Science 74:578. 1931. Reprinted in Language in Culture and Society. Dell Hymes, ed. New York: Harper and Row. p. 128. 1964.

Saunders, Barbara A. C. The Invention of basic color terms. Utrecht: ISOR (Interdisciplinary Social Science Research Institute). 1992.

Saunders, Barbara A. C., and van Brakel, Jaap. Re-evaluating Basic Color Terms. Cultural dynamics 1:359-378. 1988.

Stanlaw, James. Japanese English Language and Culture Contact. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. 2004.

Stanlaw, James. Review of Theorizing the Americanist Tradition, by Lisa Valentine and Regna Darnell. Language. (in press). 2000a.

Stanlaw, James. SAWAYAKA TASTY, I FEEL COKE!: Using the Graphic and Pictorial Image to Explore Japan's "Empire of Signs." Journal of Visual Literacy 20(2):129-175. 2000b.

Stanlaw, James. Two Observations on Culture Contact and the Japanese Color Nomenclature System. in Color Categories in Thought and Language. C. L. Hardin, ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1997.

Stanlaw, James. Color, Culture, and Contact: English Loanwords and the Problems of Color Nomenclature in Modern Japanese. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1987.

Stanlaw, James, and Yoddumnern, Bencha. Thai Spirits: A Problem in the Theory of Folk Classification. In J. Dougherty, (ed.), Directions in Cognitive Anthropology. Urbana, IL:University of Illinois Press. 1985.

Whorf, Benjamin Lee. Language, Thought and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. John Carroll, ed. Cambridge: MIT Press. 1956.

Whorf, Benjamin Lee. "The Relation of Habitual Thought to Language [1939]." in Language, Thought and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. John Carroll, ed. Cambridge: MIT Press. p. 134-159. 1956.

World Color Survey. Summer Institute of Linguistics/ University of California, Berkeley. 1991.