Return to MODULE PAGE

Introduction to Chain Codes

Lionel (Lon) Shapiro: Author

David L. Anderson: Author

Is it possible to design a computer system that can "perceive" objects in the world? If it is possible, one important ability that the machine must have is to determine the shape of an object and to determine when two objects have the same shape. How might a computer program accomplish this task? We are going to explore one type of program that can accomplish this task.

Imagine someone shows you a simple object. Later they ask you to pick out that object from a "line-up" of other objects. One strategy you might adopt would be to focus on remembering one or more salient attributes that you can pick out from viewing the object. These might include: shape, color, texture, etc.

Examining this figure we find an easily identifiable shape. That is, we can name this shape in a way that would convey meaning to others -- 'triangle.' By doing this, we are using a model (for the shape of triangles) that we can easily refer to with a word in our language.

When you learned about this shape early in your development, you may have been told that this shape has "three sides." Here our model is defined in terms of boundries between the object and its environment (in this case, the background). This model of the object can then be used for reconstruction (draw this object) or recognition (identify this shape).

Following this approach, we can construct a computer program to reconstruct or recognize shapes. In order to do so, we need to have a specific representation (encoding scheme) for our shape. For simple objects, whose construction and identification are based on boundries, we can use a chain code representation.

Absolute chain codes

When drawing a triangle, you might start at one vertex (corner) and proceed to draw three straight, connected lines, such that you return to the starting vertex with the third line drawn. If you were to try to communicate what you were doing to someone unable to see your pad, but who is able to draw on their own pad, you might say something like, "starting with the pencil at one point on the pad, move in a straight line toward the top-center of the pad for about one inch, then continue toward the lower-right corner for another inch without lifting the pencil. etc." These instructions provide the listener with a loosely defined rule that can be used to reconstruct your shape.

Instructions like this, however, are not very precise. If our goal is to be able to draw a wide range of different shapes and if we want to be able to draw them on any piece of paper, then we need to be more systematic in the directions that we give. The directions ought to be clear and unambiguous and they must offer an adequate range of alternatives -- as many directions as we are likely to require to draw the shapes that interest us.

Conveniently,

we are already familiar with a system of directions that begins to fit

the previous description: The points of a compass. Here we have a range

of eight different directions that we can use to tell people how they

are to move. Say we want to communicate the shape, size and orientation

of a two square mile section of a city that will be receiving a new

water system. First, we pick a starting point and then we tell them

were to go to traverse the perimeter of this designated section. The

directions might go something like this:

Conveniently,

we are already familiar with a system of directions that begins to fit

the previous description: The points of a compass. Here we have a range

of eight different directions that we can use to tell people how they

are to move. Say we want to communicate the shape, size and orientation

of a two square mile section of a city that will be receiving a new

water system. First, we pick a starting point and then we tell them

were to go to traverse the perimeter of this designated section. The

directions might go something like this:

Start at the corner of 5th and Main. Go west on 5th St. for 6 blocks. Go north on Maple St for 12 blocks. Go east on 17th St for 6 blocks. And go south on Main St for 12 blocks, which brings you back to the corner of 5th and Main.

The points of the compass give us an absolute set of reference points, because each direction is fixed by the Earth's magnetic fields. Thus, the "North" direction always points to a specific point in the frame of reference and is independent of which way we might be facing. Chain codes that are created using absolute points of direction are called absolute chain codes.

Absolute chain codes do not need to be fixed to anything as large as the whole earth, however. We can also fix the direction points to something smaller (like a piece of paper for example, or your computer monitor). If we do that, it is natural to make the top of the paper (or monitor) "N", the bottom "S", and so on. Once we've designated the offical "North" end of the paper, then it doesn't matter which direction we are facing as we look at the paper. "N" will always be in a fixed (absolute) direction in relation to the dimensions of the paper.

If the shape we are encoding is a large one, then a city block might be the appropriate unit of measure. But if we are to encode a smaller shape, like the triangle at the top of this page, we must use a smaller unit of measure. Let's use one inch as our unit of measure and the points of the compass as our directions. "North" will be fixed at the top of the paper / monitor. The size and shape of the triangle, then will be encoded with a string of directional letters. To interpret such a string, we will follow the following rule:

For each directional letter(s) that is written down (N, SE, W, etc.), move the pencil in that direction for a distance of one inch*. If the pencil is to be moved in the same direction for more than one inch (let's say, 3 inches), then the directional letter must be written more than one time (write: "w, w, w,"). Directional letters can either be written in a vertical column or on a horizontal line with commas separating the letter(s).

*[Note: For diagonal directions, the distance will be slightly longer than one inch -- for reasons that will be explained below.]

Using this convention, we can then represent the size and shape of an object as a chain code -- that is, a set of directional codes, with one code following another like links in a chain. Let's return to our triangle. The vertices (or corners) we will label v1 - v3. To begin we determine a starting point. Let's start at v1, going in a clockwise direction. First we move one inch in a NE direction, moving from v1 to v2. Then we move SE one inch to v3. Finally, we return to v1 by moving W one inch. (On many monitors the sides of the triangle will look longer than one inch.)

The chain code that we just produced is an algorithm that gives a symbolic representation of the triangle's shape, size and orientation. This information also provides precise rules for reconstructing that figure in a drawing. We will typically write the chaincode in one of either two ways. Either as

|

NE |

or as |

NE, SE, W |

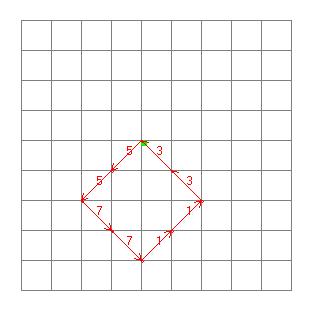

Now it is your turn to create a chain code for the figure below. Starting in the lower right hand corner, and moving clockwise, write the chain code for this shape on a piece of scratch paper.

|

|

After you've written down the complete chain code, click the button that says "Completed Chain Code" below, and see if you got it right.

Using numbers in writing chain codes

Since

chain codes provide an algorithm for

representing the size and shape of an object, it is possible to build a

machine that

is capable of encoding that information. But algorithms cannot be implemented

in a computer program using just any coding system. It must be a language

that the computer can recognize. Since digital computers typically

use a numerical system for storing information (everything is coded

in "O's" and "1's") it will be a step in the right

direction to modify our directional system to a numerical system rather

than a letter system. Computer programmers who write chain codes based

on an eight-way directional system, typically represent those eight

directions using the numbering scheme at the right.

Since

chain codes provide an algorithm for

representing the size and shape of an object, it is possible to build a

machine that

is capable of encoding that information. But algorithms cannot be implemented

in a computer program using just any coding system. It must be a language

that the computer can recognize. Since digital computers typically

use a numerical system for storing information (everything is coded

in "O's" and "1's") it will be a step in the right

direction to modify our directional system to a numerical system rather

than a letter system. Computer programmers who write chain codes based

on an eight-way directional system, typically represent those eight

directions using the numbering scheme at the right.

From now on, we will use this numbering system for writing absolute

chain codes. The "North" (or the "top" of the page

or monitor) will be represented by the number "2", "South"

is "6", "West" is "4", "East"

is "0", and so on.

From now on, we will use this numbering system for writing absolute

chain codes. The "North" (or the "top" of the page

or monitor) will be represented by the number "2", "South"

is "6", "West" is "4", "East"

is "0", and so on.

It is now time to use an interactive java program where you will get to work with chaincodes. When you go to the Java program, you will find that the objects are all located on a grid. This is to make it as convenient as possible to apply the units of measure to the objects. With the eight-direction system that we are using, a chain code can capture the shape of any object that can be drawn by connecting together intersection points on the grid. Each move will take us from one intersection point on the grid, to another. Each horizontial and vertical move is of 1 unit length and each diagional move is slightly bigger than 1 unit in length (its length is the square root of 2, to be precise).

You should now be familiar with absolute chain codes. But there is another type of chain code that also has important applications. We turn to it next.

Relative chain codes

There will be times when absolute chain codes won't do the job. Either, because no absolute point of reference is available or because absolute chain codes are not capable of doing the job that needs to be done. In such cases, using a relative perspective might be preferable.

Suppose, for example, that you had no working compass or other system for naming directions in a global frame of reference. This is easily imagined by closing your eyes and listening for a specific sound (say footsteps of an approaching friend). You may be inclined to describe the direction with respect to your body, that is, you may hear your friend approaching from your right. Note, this system of direction naming is based on positions relative to your current orientation. If you were to do a quick "about-face," your friend would appear to be approaching from your left in this example.

It

is possible to base an eight-directional coding system on relative directions.

Each of the eight directions will be defined in relation to a

moving perspective. Think of it this way. Imagine that you are driving

a car around the perimeter of the object, marking a line behind you

as you go. From any given point you have eight options. You can continue

to go forward ("F") in the same direction that you have been

going, you can go backward ("B") in the opposite direction,

you can turn to the left ("L") or to the right ("R").

These are the four main points of the compass. The other four directions

are derived from the four basic ones, as can be seen in the compass

to the right.

It

is possible to base an eight-directional coding system on relative directions.

Each of the eight directions will be defined in relation to a

moving perspective. Think of it this way. Imagine that you are driving

a car around the perimeter of the object, marking a line behind you

as you go. From any given point you have eight options. You can continue

to go forward ("F") in the same direction that you have been

going, you can go backward ("B") in the opposite direction,

you can turn to the left ("L") or to the right ("R").

These are the four main points of the compass. The other four directions

are derived from the four basic ones, as can be seen in the compass

to the right.

Now take a try at producing a relative chain code for the same figure that you worked with above. Remember this time, the "directional compass" does not stay fixed in one position. The "F" does not always point "up". The "F" points "forward" in whatever direction YOU are moving as you mentally traverse around the perimeter of the object. Starting in the lower right hand corner, and moving clockwise, write the relative chain code for this shape on a piece of scratch paper. Keep in mind: The directional code representing any particular section of line is relative to (and thus dependent upon) the directional code of the preceding line segment.

|

|

Write down the relative chain code for this figure on a piece of scratch paper. When you've finished, click the button that says "See Completed Chain Code" below, and see if you got it right.

Did you get it right? It is common for people to get the very first letter wrong (even if they get all the others right). There is a reason for this. When you begin making the chain code, you locate yourself (mentally) in the lower righthand corner and you tend to orient yourself in the direction that the first line segment is moving. So it feels natural to many people to put an "F" for the first line segment. However natural that might be, you aren't allowed to do it that way. You don't get to choose your orientation. Remember the hint above:

The directional code representing any particular section of line is relative to (and thus dependent upon) the directional code of the preceding line segment.

What this means is that relative chain codes have one rather tricky element. The directional code for the first line segment cannot be determined until you know what the directional code is for the last line segment. That means that you either have to look back to the preceding line or you have to leave the space for the first code blank and wait until you have finished the rest of code and then fill in the direction for the first line segment. Given the direction that the last line segment was moving, a right turn ("R") was required to place the first line segment moving in the proper direction.

Did this all make sense? If not, try to do the chain code again. When you've come full circle and return to the "start" button, don't stop there. Make one more move as you turn the corner. That move around the corner (a move to the "right") is the first directional code for the figure. Since the direction of any line segment is relative to the orientation of the line preceding it, we must consult the preceding line segment.

Now let's try a relative chain code for the triangle.

|

|

|

Write the down the relative chain code for this figure on a piece of scratch paper. When you've finished, click the button that says "See Completed Chain Code" (below) and see if you got it right.

Just as we did with absolute chain codes, we can modify the directional

system that we use with relative chain codes, using a numerical system

rather than a letter system. Computer programmers who write relative

chain codes based on an eight-way directional system, typically represent

those eight directions using the numbering scheme at the right. The

"forward" direction that was represented with an "F"

is now represented with the number "2," "Backwards"

is "6," "Left" is "4," "Right"

is "0," and so on.

Just as we did with absolute chain codes, we can modify the directional

system that we use with relative chain codes, using a numerical system

rather than a letter system. Computer programmers who write relative

chain codes based on an eight-way directional system, typically represent

those eight directions using the numbering scheme at the right. The

"forward" direction that was represented with an "F"

is now represented with the number "2," "Backwards"

is "6," "Left" is "4," "Right"

is "0," and so on.

We now have two different methods for recording the shape of an object, one using an absolute point of reference, the other using relative reference points. The next step is to consider how a computer program might encode this information and make use of it to "recognize" objects.

Machines that do chain codes

One of the topics that we've been exploring is that of "machine vision." How might a machine be made to process visual information about the world? Given our present discussion of chain codes, we might ask: What kinds of visual information could a machine acquire using chain codes? As you may have already deduced, each type of chain code has its own advantages.

One of the strengths of the absolute chain code is that it carries information not only about the size and shape of the object but also about its rotation. Suppose we want to encode the information about the size and shape of the triangle, but also about the position of the figure on the page. An absolute chain code can distinguish between the triangle on the left (below) and the one on the right, that has been rotated 180 degrees.

|

|

|

The absolute chain code for the triangle on the left is: 4,1,7. For the one on the right, it is: 0, 5, 3. They don't share even one number in common. This is because the rotation of the triangle as well as the size and the shape are being represented in the code. So, if we want to build a machine that can preserve the orientation of an object (its rotation) as well as its shape and size, then the machine would need to represent the object with an absolute chain code.

Relative chain codes do not behave in the same way. The relative code for the first triangle is 7, 7, 0. The code for the triangle on the right will also be 7,7,0 if the starting point remains the same (as shown by the words "start" above). Things only change slightly if we move the starting point to the right-angled corner of the triangle. The code then becomes: 0, 7, 7 regardless of whether the base of the triangle is pointed up or down.

The similarity in these chain codes has a beneficial feature, one that our machine can take advantage of. Since the numbers that are used are the same, a computer can be programmed to compare the chain codes of two different objects and determine if they are the same size and shape. Here is how it works.

Comparing chain codes

Since the starting point for a relative chain code is completely arbitrary, we can shift the numbers around to reflect different possible starting positions. Now, we must be careful not to change the serial order of the numbers, because that is an essential part of the way the shape and size of the object is represented. One thing we can change, however, is which number we start with as we generate the series. So, let's say that our machine is trying to determine if the following two chain codes represent objects that are the same size and shape. Let's take the two relative chain codes that we created above. Here are the triangles and the chain codes:

|

Triangle #1 |

Chain Code #1 |

Chain Code #2 |

Triangle #2 |

|

7 |

0 |

|

|

7 |

7 |

||

|

0 |

7 |

If our computer program compares the numbers in these two lists, it will not produce a match. The top and bottom numbers don't match.

However, the fact that they don't match up could be the result of nothing more than the codes having been started at different vertices of the triangle. So, the only way to tell for certain whether or not the two objects are the same size and shape, is to change the order of the numbers on one of the chain codes, trying every possible starting point. You can visually see how this would work by pulling a number off the bottoom of the chain and moving it to the top.

This preserves the serial order of the numbers. You can cycle through the entire code this way, shifting the starting point one line segment at a time. If you cycle through each number in the code, you will be able to see if the two codes eventually "line up" so that you can visually see (as in column 3 above) that the two codes are exactly the same.

If we wanted to give a machine the ability to compare chain codes, a fairly simple program can be written that can determine whether or not two chain codes are exactly the same. This would give the machine the ability to judge that two shapes were the same, even if they were rotated quite differently.